HAITIANIDENTITY

Dajabon Region, northern border of the Dominican Republic, between the Dominican Republic and Haiti, the richest and the poorest Caribbean countries in the western hemisphere. Active in this area is Solidaridad Fronteriza, an organization run by Father Regino Martinez, a Dominican Jesuit priest who for years has been fighting for human rights along side these migrants and Haitian deitrabajadores. Batays, or communities of illegal Haitian migrant workers, are located near the border where many of the Dominican plantations are found.

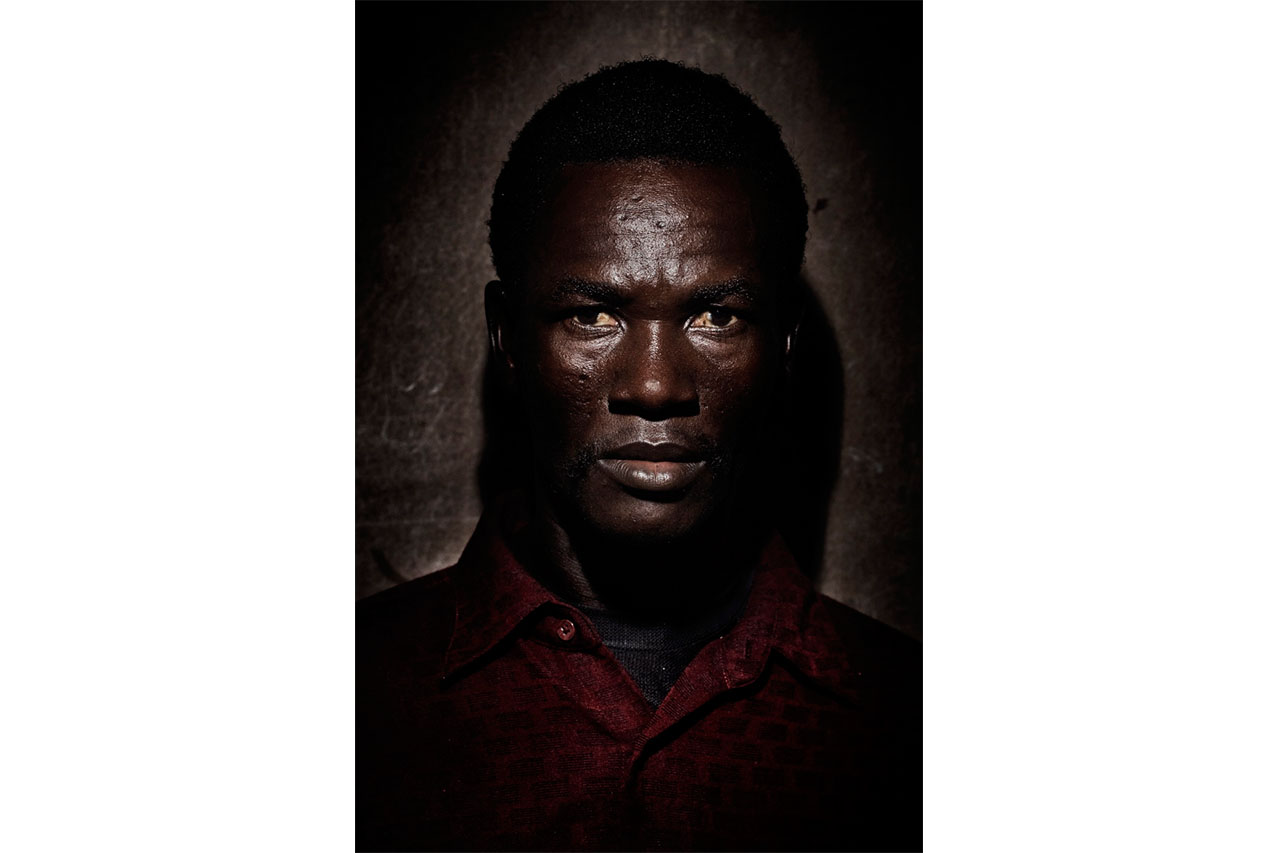

The flux of Haitian migration is continuous and has been going on for generations but the situation regarding civil rights has remained unchanged. The Dominican Republic does not provide for any form of legalization for these migrant workers; it does not even recognize as citizens Haitian babies born in the country. There is a sort of apartheid which condemns Haitians to a condition of systematic exploitation. Without documents they cannot move about freely; their only alternative is to corrupt the National Guard and the military police stationed at the road blocks located throughout the country, and in particular, at the frontier crossings. The result is a form of contemporary slavery based on the annulment of one's identity. Jacques: a young Haitian who lives with his wife and five children in the Ranchadero batay. He left Haiti after his father died, in search of work, to support his family. He earns 180 pesos per day, the equivalent of US$5.00. "Life is difficult for us Haitians because the Dominicans don't like negroes".

Jan Claude: he came by himself and brought his family later: "My children don't have access to health-care and can't attend school because I have no documents, I'm 'irregular' ".

Anita arrived from Fort Liberte a year ago October. "I return to Haiti to visit part of my family that is still there, but the trip is dangerous and expensive; I need money to corrupt the military police stationed in the area." The Hato del Medio batay is very well organized and run with precise internal rules so that members of the community are not caught in situations that are illegal. Any new arrival can settle at the batay as long as he has references. No one without references is allowed into the batay in that an unidentified person is considered to be a potential source of conflict. The Dominican community tries to avoid any situation which would serve as a pretext to local authorities to justify oppressive behavior. Two houses were burned down a few weeks before my visit to the batay. For some time now the mayor has been preventing the Haitians from building a church and a center for social activities for fear that socializing will foster coesion of the community. The relationship between Haitians and Dominicans has been marked by the massacre perpetrated in 1936 by the dictator Trujillo. La frontera estas muy nublada, he said, meaning that there were too many negroes, too many Haitians. He ordered ethnic cleansing which resulted in the Dominicanization of the border which then officially remained closed until the 80's. According to Father Regino Martinez, "The relation between Haitians and Dominicans is based on prejudice and not on values. The process of Dominicanization carried out by the Dominican authorities has transferred to the population a distorted view which foments racism and xenophobia; for a Dominican, Haitians are thieves and for a Haitian, Domenicans are racist assassins. Trujillo promoted anti-Haitian ideology which has become an integral part of the Dominican identity to the point where that which gives identity to Dominicans is the negation of Haiti". This has become legitimized by law which considers Haitian migrants "in transit" and, despite the fact that their work is the motor of the national agricultural economy, they are barred from obtaining regular documents. To cope with anti-Haitian sentiment various Haitian communities have been organizing workers' association backed by Solidaridad Fronteriza. They have been creating individual identification cards as well as data banks that collect photographs and information about its members, including the name of the farm on which they work, employer, personal data, place of origin and number of years in the Dominican Republic.

Jonny Rivas is a Haitian volunteer who works in the Juan Gomez, Hatodel Medio, La Reforma and Cerro Gordo batays. His job, which he considers a mission, is to promote and organize the associations through which migrant Haitians vindicate their own identity and rights. "The association provides protection and security, not money. The association"s identification card is a means by which members may assert themselves as individuals and as a group; it permits them to affirm their identity as workers and as human beings".